OKLAHOMA CITY (Free Press) — Crowning the southern skyline of Oklahoma City with an epic half-dome, the First Americans Museum will open its doors to the public this month in a much-anticipated grand opening.

The millennia-long history of America’s Indigenous people will be jointly told in a place built by them and for them – making the museum a unique historical moment in itself.

The museum leaves no stone unturned in its effort to elucidate the stories of First Americans. Artifacts from ancient sources stand only feet away from art made by contemporary creators, and the stories of the Modoc Nation from the Pacific Northwest are told right next to the Great Plains tribes of the Comanche and Kiowa.

Together, the thirty-nine tribes that form the core of the First American Museum have created a place of dignified reflection that promises a thorough and respectful survey of the history of the First Americans.

The Arts

with Devraat Awasthi

Museum’s development

The story of the First Americans Museum is a tumultuous one by all accounts. In 1994, the Oklahoma State Legislature created the Native American Cultural and Educational Authority (NACEA) with a mandate to construct and operate a Native American cultural center in Oklahoma City. The original funding arrangement, according to Deputy Director Shoshana Wasserman (Thlopthlocco Muscogee), was to split the cost evenly between the federal government, the state government, and the private sector in thirds.

Various intervening events, including Hurricane Katrina, the wars in the Middle East, and political changes, altered the calculus for funding. Of the $33 million authorized by the federal government to be spent on the (formerly) American Indian Cultural Center and Museum, only about $7 million was realized. The State of Oklahoma, suddenly the museum’s chief benefactor and overwhelmed by recession and tornado disasters, similarly failed to meet its financial obligations. Even the city government unanimously voted against taking on the burden of funding the museum’s operating deficit.

“Thank goodness for a subsidiary of the Chickasaw Nation!” said Wasserman. After the various failings of federal, state, and local governments, the Chickasaw Nation agreed to fulfill the operating deficit of the museum and received the right to purchase and develop the surrounding property. Wasserman credits Governor Bill Anoatubby of the Chickasaw Nation, who is also the chair of the NACEA with saving the project, saying he “has been steadfast all these many years in making sure that this is a world-class institution, that it never lost its original mission or intent, and what it set out to do. We’re eternally grateful.”

Wasserman also expressed the museum’s excitement for the planned development in the area, and although exact details were withheld, she described future plans in which the museum would be an anchor for a nationally oriented destination.

Arrival

Today, the joint venture of the Oklahoma City government and the Chickasaw Nation stands proudly along the southern bank of the Oklahoma River. The glittering glass and steel that now adorns the southside, however, took more than a decade to complete. The land on which the museum sits has a story as well. “This was oil field number one!” explains Executive Director James Pepper Henry (Kaw/Muscogee). Thirty percent of the world’s oil supply and 60% of the nation’s oil came from the Oklahoma City Oil Field.

This history entailed ecological and ethical difficulties that the First Americans Museum undertook. “By building this center, we’ve healed the land. We mitigated all those issues, cleaned up this site, and so in a way, it’s kind of beautiful that it took Native people to come in here, to heal this place, and get it back into balance,” said Henry. According to Wasserman, “We had to cap oil wells to current standards, we had to locate oil wells . . . it took a full year to do the site remediation. We removed over 7,000 tires, box springs, all kinds of things. It became a dumping ground for a period of time.”

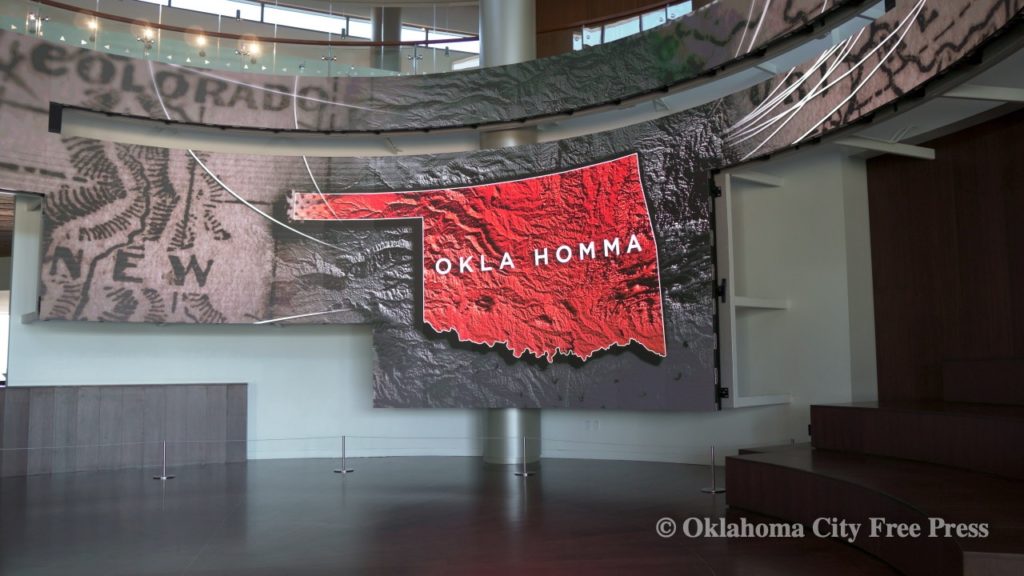

Part of the process of reclaiming the land was a ground blessing ceremony in 2005, where 39 tribes brought ashes from the ceremonial fires of their original homelands as a new fire was lit, the ashes of which now sit in the OKLA HOMMA exhibition.

Architectural symbolism

The history of the First Americans Museum enhances the physical beauty of its building. “A lot of symbolism has gone into the design of this building,” said Henry. The building was co-designed by Johnson Fain of Los Angeles and Hornbeek Blatt of Edmond, Oklahoma.

The gigantic mound feature recalls the ancient cities of the Caddo people in eastern Oklahoma, most prominently featured in the Spiro Mounds site. “Spiro was bigger than London at the time of the arrival of the Europeans!” said Pepper Henry. The mound was built with over 500,000 cubic yards of earth capped at an apex that gives visitors a unique view of downtown Oklahoma City. The mound, planted with indigenous grasses like buffalo grass and bluestem in terraced baskets, is mirrored by the glass and steel building in an effort to merge the past and present.

The most remarkable aspect of the museum’s design, however, is the “cosmological clock.” According to Pepper Henry, on the winter solstice every year, the setting sun will shine perfectly through a tunnel cutting under the mound. On the summer solstice, the sun will set at the peak of the mound. On the equinoxes, the sun will shine through a hand symbol marking the entrance and center of the museum. “The amazing thing about it is the architects and the engineers were trying to figure all this out, and even with all the computers they had, it was still very difficult to figure this out, and they were amazed at how the ancients could figure this out, without sophisticated computers.”

The entrance to the museum is marked by the Remembrance Walls, which “acknowledges that there were always original Native inhabitants here, living in this place, there were several tribes that have always been here,” said Wasserman. “It also acknowledges those that were on the Removal – many different removal paths here – and did not survive, and it celebrates those of us that are the descendants of those who made that courageous journey and are here today.”

Past the Remembrance Walls and inside the museum is the signature half-dome of the museum, known as the Hall of the People. Modeled after the grass lodges of the Caddo people, the Hall stands 90 feet tall and is shielded with 800 panes of inch-thick glass. “In theory, it’s weather-proof,” according to Henry.

Groundbreaking curation methods

The beauty and history of the museum, however, are overshadowed by the groundbreaking curation methods that the museum has developed. As Wasserman points out, the museum prioritizes a “first-person” perspective to curation and emphasizes storytelling from primary sources.

OKLA HOMMA, an exhibition with art and history from 39 Oklahoma-based tribes, is dotted with interactive exhibits that amplify the voices of Indigenous artists, historians, and people. These stories connect isolated, abstract historical events, like the Washita Massacre, to people from our communities, whose grandparents and ancestors survived the historical record to sustain it. For many visitors, the museum’s personalized effort to connect history to people will be powerfully emotional.

In particular, as tribal nations across the continent come to terms with the recent discoveries of mass graves in Canadian boarding schools, OKLA HOMMA’s special focus on Indigenous storytellers will give voice to the grief and anger shared by many.

Additionally, this approach sensitizes visitors to the lived feelings of survivors and descendants, and underscores the Indigenous view of time as a circular, rather than linear, arrangement, as Wasserman points out; that is, that history is constantly making itself, continuing to happen today and in front of us.

The museum’s second exhibition, WINIKO: Life of an Object, is a study in this practice. WINIKO is the museum’s most anticipated exhibition, containing pieces from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. These materials were originally removed by Mark Harrington and displayed in various museums, before being returned to Oklahoma in the First Americans Museum. “We give you a peek behind the scenes of a museum – and we’re a museum, we’re part of that process, but we are trying to indigenize the practices associated with cultural materials,” said Wasserman.

WINIKO attempts to tell the story of objects from the perspective of the objects themselves, tracing their history through the various families associated with them. The exhibition compares and contrasts museum practices towards cultural materials with the practices of Indigenous peoples, and through years of tribal consulting, attempts to meld the two.

“We and the Smithsonian are like this perfect marriage,” Wasserman told us. Because the Smithsonian possesses an immense collection of Indigenous material but is distant from the tribes of origin. Here in Oklahoma, a state with one of the largest populations of Native Americans in the country, many Oklahomans may never get the opportunity to travel to D.C.

“Where that is so powerful is that we have several different materials that we knew the descendants of the original makers,” Wasserman continued. “And, we reunited those family members with the cultural materials that maybe their great-great-grandfather made, or great-aunt made, and it was just a remarkable, emotional, terribly personal experience for the Smithsonian to actually let them do something that is pretty unheard of in the museum world. They were able to privately be reunited with the material and they were able to actually put their hands, their DNA, on the material of their ancestors, whose DNA is there. There were tears, just profound experiences.”

16 years

For Wasserman herself, who has helped shepherd the museum into fruition over 16 years, the grand opening is the culmination of heartfelt, hard work. The process of tribal consultation was particularly difficult: “How do you even begin to pick a color palette when all of our tribes are so distinct? How do you merge so many different motifs together without it being chaotic? How do you introduce languages without that being chaotic for a visitor?”

But Wasserman takes pride and joy in the end result, pointing to the cultural integrity of the museum’s all-Native staff as an example of the museum’s worthwhile goals.

She also compares the obstacles she and the museum faced – “after 12, 13 years, to think about is ‘it less expensive to demolish it or go forward’ . . . lucky it was less expensive to go forward!” – with the experiences of her ancestors, who persevered over daunting odds as well. The First Americans Museum is thus another chapter in First American history, and a testament to its resilience.

Visit https://famok.org/ for information on ticketing and visit starting with the grand opening on September 18-19.

Last Updated September 5, 2023, 10:14 PM by Brett Dickerson – Editor

The post First Americans Museum Brings Dignity to Indigenous Art and History appeared first on Oklahoma City Free Press.